- Home

- Arthur Allen

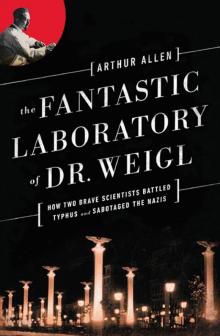

The Fantastic Laboratory of Dr. Weigl: How Two Brave Scientists Battled Typhus and Sabotaged the Nazis

The Fantastic Laboratory of Dr. Weigl: How Two Brave Scientists Battled Typhus and Sabotaged the Nazis Read online

THE

FANTASTIC

LABORATORY

OF

DR. WEIGL

HOW TWO BRAVE SCIENTISTS BATTLED TYPHUS

AND SABOTAGED THE NAZIS

ARTHUR ALLEN

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

New York | London

To Margaret, Ike, and Lucy

CONTENTS

Preface

Introduction

Chapter One: Lice/War/Typhus/Madness

Chapter Two: City on the Edge of Time

Chapter Three: The Louse Feeders

Chapter Four: The Nazi Doctors and the Shape of Things to Come

Chapter Five: War and Epidemics

Chapter Six: Parasites

Chapter Seven: The Fantastic Laboratory of Dr. Wiegl

Chapter Eight: Armies of Winter

Chapter Nine: The Terrifying Clinic of Dr. Ding

Chapter Ten: “Paradise” at Auschwitz

Chapter Eleven: Buchenwald: Rabbit Stew and Fake Vaccine

Chapter Twelve: Imperfect Justice

Afterword

Notes

Acknowledgments

Index

THE

FANTASTIC

LABORATORY

OF

DR. WEIGL

PREFACE

A few years ago I found myself in a dim corridor at the Institute of Epidemiology and Hygiene in Lviv, Ukraine, trying to persuade Dr. Oleksandra Tarasyuk, the institute’s polite but recalcitrant director, to let me watch the feeding of the lice.

Why, one might ask, would anyone come all the way to Ukraine to look at lice? They are, after all, common loathsome insects, synonymous everywhere with disease and filth, wretchedness and neglect. To the naked eye, Dr. Tarasyuk’s lice were no different from the ones that I and millions of other parents combed from the scalps of our children during elementary school infestations. I had once or twice examined my children’s cohabitants under a microscope and found them to be surprisingly intricate, greasy-brown creatures whose guts contained tiny but distinct canals of blood.

But the lice of 12 Zelena Street, Lviv, were not quite ordinary creatures. For one thing, they were body lice (Pediculus humanus humanus) rather than head lice (Pediculus humanus capitis). The two insects, varieties of a single species, are remarkably similar; even geneticists have trouble parsing their essential difference. Both nourish themselves by poking an exoskeletal needle into the warm skins of humans and employing the musculature of their tiny proboscides to extract our blood. But for reasons that biologists have yet to understand, there is one fundamental distinction between head lice and body lice: head lice are a nuisance, but only body lice transmit one of humankind’s most fearsome diseases, typhus. Body lice are thus players, in a way that head lice have never been, in some of the great tragedies and most horrendous pages of history. Few organisms have been as deadly to doctors and medical researchers as typhus. This is perhaps not surprising, because the sick shed lice, which are fussy about heat and cold and abandon the body once temperatures fall below 98 degrees Fahrenheit or rise above 102 degrees, desperately searching for a new home. Each laboratory in the fight against typhus had its martyrs, and publications about the disease were inevitably dedicated to fallen colleagues. This explains why the lice of Lviv led such a charmed existence, spending most of their lives swarming together in the comfort of heated wooden cabinets, unlike the rootless lumpen proletarians that burrow, for a brief while, in the hair of schoolchildren.

Like many scientists who spend careers in close proximity to lab animals, Dr. Tarasyuk felt quite protective of hers. “It’s very difficult to keep this population alive,” she told me in a remorseful tone. “They need particular temperature levels at different stages of their lives. They feed only once a day. And we have to make sure that the feeders are healthy.”

And what do these lice eat? Human blood, of course. And how do they procure it? Why, by being placed in cages on the legs of human beings. The feeders at the institute, each paid a small sum for their sacrifice and blood donation, were mostly lab technicians. The idea of letting me, a stranger who didn’t even speak Ukrainian, into the lab filled Dr. Tarasyuk with horror. I could give the lice a disease! I could threaten the survival of the colony! She could lose her job! “Come back the next time you are in Lviv, but give us more warning,” she told me with a frown. “We would love to see you again.”

Afterwards I stood outside the rather plain, five-story, Bauhaus-influenced building for a few moments and tried to conjure up a picture of its past. The lice of 12 Zelena Street are the descendants of a colony bred seven decades ago by the zoologist Rudolf Weigl, who crossed lice picked from the bodies of Russian prisoners of World War I with those nestled in the robes of Ethiopian highlanders. With these lice and a lot of ingenuity, Weigl in the 1920s created the first effective vaccine against typhus, a disease that terrorized the world, inspired the creation of Zyklon B gas, and provided a pretext for the worst human crimes in history. Weigl’s discovery drew global notice. Nobel laureates trod the corridors of his institute to study his techniques and pay homage to him. Agents from the Nazi SS and the Soviet NKVD sniffed around the halls of his institute; Nikita Khrushchev, later the Soviet premier, and Hans Frank, the Nazi governor of Poland, appeared at his doors, soliciting Weigl’s services.

The lice were all that remained of a fantastic research laboratory where Weigl had devised his vaccine with an almost surrealistic series of manufacturing techniques. During World War II, Weigl’s laboratory became the spiritual center of the city, protecting thousands of vulnerable people who worked in it. Weigl was a bit like Oskar Schindler, the real-life hero of Steven Spielberg’s film Schindler’s List, except that to get on Weigl’s list, you had to strap many matchbox-size cages to your leg with a thick rubber band. In each cage, there were hundreds of lice that fed on your blood. The survivors of Weigl’s laboratory became famous mathematicians and poets, orchestra conductors and underground fighters.

The one who most captured my imagination was Ludwik Fleck, a biologist in his own right, and also a philosopher of science. While working as Weigl’s assistant, Fleck had incubated a captivating theory of scientific knowledge and laid it out in a 1935 book, Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact. Today, Fleck is well known to sociologists and historians of science. Thomas Kuhn, the famous theoretician of knowledge who gave us the term “paradigm shift,” borrowed heavily from Fleck’s thought in writing his 1962 classic, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.

Fleck’s writing drew me because of his penetrating analysis of the human at work, his observations enlivened by clarity, humor, and earthiness. He showered empathy upon his subjects, whether they were medical researchers, women besotted with Parisian fashions, or medieval astrologers. Reading Fleck gave me a sudden sense of intimacy with the thought patterns of ancient and otherwise inscrutable people. He made the past bubble to life by showing the integrity of its thought systems, however wrong or bizarre they seemed to us. And he made me realize that although we live in a world separated by an almost infinite number of different mindsets, recognition of this fact can enable us to understand one another. In his day job, Fleck practiced traditional scientific reductionism, limiting the variables in order to resolve diagnostic problems. His job was to detect the invisible particles that lurked behind the familiar events of everyday life—the bacteria and antibodies that helped explain a cough, a fever, a sickly child. His philosophy, by con

trast, did just the opposite: it cast a familiar light on the arcane thought patterns of the strangers who surround us in the present and the past.

Fleck’s anthropological observations of science had allowed him to rise above tragedy, to gain an almost spiritual perspective amid a storm-tossed life. He had served the Habsburg Empire as a medical officer during the Great War, endured anti-Semitic discrimination in the 1920s and 1930s, then survived the Holocaust, the intrigues of postwar communism, and the hush-hush of a Cold War bioterrorism lab in Israel.

Fleck’s medical specialty was immunology, or, as it was known in the first part of the 20th century, serology—the changes in the blood that helped doctors diagnose and treat infections. Blood had always been a mysterious and therefore a symbolic substance—“a humor with distinctive virtues,” as Mephistopheles says in Goethe’s Faust. That book intrigued Fleck, who believed that the immunological paradigm of his time—blood as a battleground in which cells and antibodies fought off germs—was only the latest, culturally influenced understanding, one that reflected the period’s nationalistic quarrels. He predicted that more nuanced insights would open the way to calmer metaphors in the future. He was right, as demonstrated by recent studies of the multifaceted role of bacteria in our individual “microbiomes,” which show that we are walking superorganisms whose life processes depend on interactions with trillions of bacteria inside of us.

In short, more than just lice had drawn me to Lviv. So much decision and thought and sacrifice had taken place here in this far-off corner of Europe near the Carpathian Mountain chain. The city had been occupied by ten different powers during eight decades. Its population had been murdered and expelled by the hundreds of thousands in the 1940s, and the remarkable accomplishments of these forgotten people had faded along with their bones. Now I watched its streets fill with buses and trams and with Ukrainian citizens, each individual possessing a feeling of belonging, no doubt, though they inhabited a city formed by people of languages and faiths that were absent now. It was as if Lviv’s human population was fungible, its lice the only permanent colony.

The setting of this book is the fight against typhus during World War II. Nazi ideology had identified typhus, which is spread by lice, as a disease characteristic of parasitic, subhuman Jews. The Nazi medical profession whipped itself into a terror of typhus and took outrageous measures ostensibly to combat it. These included the walling in or closing off of Jewish ghettos in cities like Warsaw, Kraków, and Lviv, assuring that the disease would indeed spread, but only among Jews. Learned German doctors convinced themselves that it was better to kill the Jews than to allow them to contaminate others.

Weigl and Fleck thus found themselves fighting on two fronts. The Third Reich kept them alive because it needed their expertise on typhus, but in keeping them alive, the Nazis could not stop them from helping others. Fleck and Weigl found the calm to practice medical science—and to sabotage the goals of the oppressor. For their German bosses, meanwhile, the fight against typhus became a theater of medicine gone wrong. But there were degrees of wrongness and moral failure. Weigl’s boss was a pragmatic army doctor, Hermann Eyer. Fleck, meanwhile, had to work for the notorious Dr. Erwin Ding of the SS, who ruled over a fiendish corner of the Buchenwald concentration camp, a laboratory of ethical choices that would go on trial at Nuremberg.

In Lviv, there are no statues of Weigl or Fleck, and no monuments to their work. The lice colony is nothing more than a scientific curiosity. After World War II, a thick layer of neglect settled upon the subjects of this book. What Fleck would have called the “thought collectives” of typhus research, and those of Polish and Jewish Lviv in general, no longer exist. This book attempts to clear away the dust and bring them back to life.

INTRODUCTION

Late afternoon at the Buchenwald concentration camp, on a mountainside six miles northwest of Weimar, Germany. A cloudless day: August 24, 1944. As always, the wind sweeps ceaselessly down the slope, buffeting the barracks, the Gestapo bunker, the hospital, and the typhus experimental station, blustering through the parade ground and the ditches where road crews of matchstick inmates lift pick and shovel accompanied by the capo’s cruel barking of orders. It is a hostile wind that penetrates every fold in the clothing “as if it they had placed it there with the purpose of making people feel miserable,” one prisoner will say. In the winter it “seemed to come direct and unimpeded from the North Pole.” In this, the eighth summer of the concentration camp’s existence, it tosses grit into the eyes and mouth.

On the second story of Block 50, a stone-and-stucco building toward the bottom of the hill upon which the camp stands, Ludwik Fleck runs tests on a series of blood samples sent over from the experimental block. He is one of a few dozen scientists from around Europe who have been captured and brought to this building in Buchenwald to help the SS produce typhus vaccines for the protection of German troops at the eastern front. For two years the news from the front has been bad for the Nazis, and the trenches are past lousy. Fleck is 48, a slight, myopic, balding man with an expression of skeptical confidence. His slave scientist colleagues respect his skilled hands and knowledge of the world that swims under the microscope lens. So do the Nazi doctors who hold his life in their hands. From his lab bench, copiously appointed with all the equipment that the looted universities of Europe have to offer, Fleck can see through a window and double barbed wire to the Little Camp, where the truly doomed inmates live. Many of them are Jews like him, stumbling along on skeletal legs amid the dirt, lice, and shit.

He hears the faint hum of the planes, a hopeful sound that is more common now that the Luftwaffe, the German air force, has surrendered the skies. Then the air-raid sirens sound and unexpectedly, the shriek of explosions batters his eardrums and he falls, tossed to the wooden floor. At last, vengeance and a direct hit! The force of the blast blows open doors and shatters windows. Beakers and petri dishes tumble off laboratory shelves, fire and mud and hot metal leap into the sky. Electricity stops, silencing the lab’s centrifuges; with panicked shouts, the SS duck and run and pitch themselves into their bomb shelters. The prisoners, with nowhere to hide, jump into trenches at the edge of the camp. D-day is two months past, Paris is on the verge of liberation, and SS control of the concentration camps finally seems to be weakening. Forty bombers of the Eighth U.S. Air Force have raided the military industries adjacent to Buchenwald. Their primary target, the Gustloff-II factory, where 3,500 camp inmates make carbines for the German army, lies in rubble after the hourlong strike. A few incendiary bombs land on the camp itself, and one sets fire to the Effektenkammer, the building where the stolen possessions of the prisoners are washed and sorted, along with the camp laundry. From there, the fire catches in the dead limbs of a large gray tree called the Goethe oak.

This spot in central Germany was called the Ettersberg, after the French, hêtre, for beech. In the early 19th century it was a wild and woolly forest, 1,500 feet above sea level, part of a royal hunting ground where German poets could commune with the inner Visigoth of their tree-worshipping past. But that all changed in the summer of 1937, when the SS bused in a hundred of its political enemies and ordered them to tear down the trees and rip out the stumps. A concentration camp took shape on the wind-swept slope—crude barracks and whipping posts for the prisoners; villas, gardens, and a private zoo for the SS and their children. The Nazis renamed the place Buchenwald—the beech wood.

Inmates walk in front of the Goethe oak in June 1944, with the Effektenkammer in the background. (Photo by Georges Angeli. Copyright Buchenwald Gedenkstätte.)

Having done so, they maliciously removed all the beeches, but preserved a single tree, a great oak six feet in diameter. Under this tree, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was said to have composed the Walpurgis Night scene of his Faust. The camp commandant erected a bronze plaque on the tree, an opportunity for the slaves to get a little culture while they worked themselves to death. “Here Goethe rested,” it read, “during his wanderings through t

he forest.”

As the war dragged on and the suffering of the prisoners passed beyond any understanding, a legend began to circulate that the destruction of the Goethe oak would augur the downfall of Germany. And so, as fire spread from the laundry to the oak, some wondered whether deliverance was at hand. There were many literate prisoners in the camp, but any affection for the German Romantics had been replaced with an animal sensitivity to signs and portents. The glowing embers reflected glee in the faces of the inmate bucket brigades. The bombing raid had killed 600 inmates—along with 200 SS men and their family members. But it was the symbolic oak of Buchenwald that burned now, and not Paris. Ludwik Fleck captured the mood later in an unpublished essay that was found among his papers. “Die, die you beast, symbol of the German empire,” he wrote. “Goethe? For us, Goethe doesn’t exist. Himmler killed him.”

The gift of Goethe, Germany’s best-loved poet, the flower of a thinking, creative, generous world of art and science, came close to bitter extinction in Nazi Germany. It survived, among other places, in the mind of Ludwik Fleck, the Buchenwald laboratory slave, who had elaborated a marvelous and prescient philosophy of science in the happier days of his life. Science, he wrote, was a culturally conditioned, collective activity bound by traditions that were not precisely logical and were generally invisible to those who carried them out. Scientific disciplines, such as the ones he belonged to, operated by the same arcane rules as a tribe in the Amazon or a group of government clerks. The members of each thought collective saw and believed what they had been trained to see and believe. Pure thought and logic were illusions—perception was an activity bound by culture and history.

The ideas and thinkers of the past were not wrong, Fleck wrote, but they had built their ideas upon “shapes and meanings that we no longer see.” This was not to say there was no progress, nor that one could not distinguish good science from bad. The idea of an “Aryan” or a “class-conscious” form of science, Fleck wrote in 1939—with Hitler and Stalin, champion corrupters of science, preparing to pounce on his homeland—“would be laughable if they weren’t so dangerous.” But Nazi medicine was a thought collective with peculiar fixed ideas. Fleck, as a sociologist of science, penetrated its weak points and put his insights to good use.

The Fantastic Laboratory of Dr. Weigl: How Two Brave Scientists Battled Typhus and Sabotaged the Nazis

The Fantastic Laboratory of Dr. Weigl: How Two Brave Scientists Battled Typhus and Sabotaged the Nazis